Asylum food 1861 -1900

The Lunatic Asylum Ball

When I was a nursing assistant working on an elderly male psychiatric ward in the early 1980s I witnessed patients having grand mal epileptic fits about once a week. At first I found it quite frightening, but later I became quite blasé about it, although I did wonder why they were so common.

Epilepsy only began to be successfully treated in the late nineteenth century and early treatments such as bromine were very sedating. It was only with the advent of phenytoin in the twentieth century that successful non-sedating treatments became available.

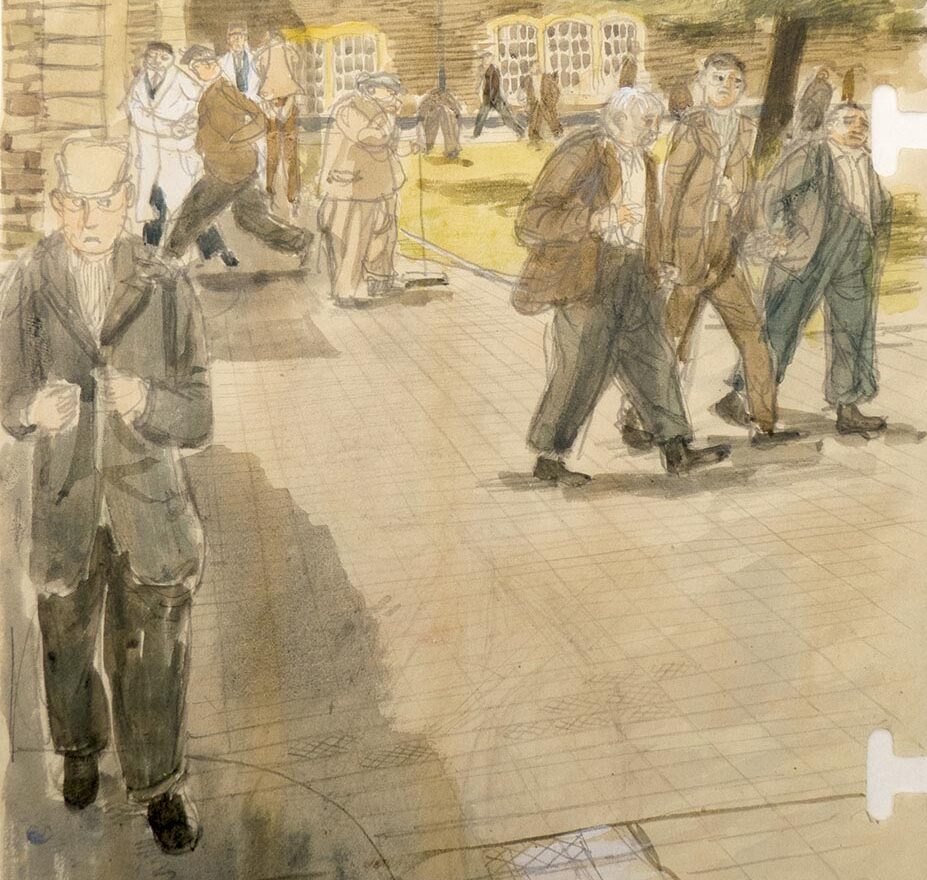

Image: Patients walking in the grounds of Bristol Lunatic Asylum, Denis Reed (RA, RWA)

Of those conditions which are now seen as non-psychiatric, epilepsy was the most common at Bristol Lunatic Asylum. The Medical Superintendent Dr Benham asserted in 1890 that there were 120 patients with epilepsy; this was about one fifth of the patient population (Early, Pauper Palace). However, just 11 patients from 1861 to 1900 had epilepsy as the primary diagnosis. In total, 562 patients were noted as having epilepsy but their primary diagnosis was most commonly given as dementia. Yet, many of their symptoms, including memory loss, aggression and confusion, seem to have been a result of their epilepsy.

Epilepsy was their main problem and is evidenced by the fact that they were housed in their own wards (male and female), presumably so they could be better observed. The table below is taken from the 1881 Superintendent’s Report and is rather shocking, showing that fits were very frequent.

| Male | Female | ||||||||

| No. of epileptics | Day | Night | Total | No. of epileptics | Day | Night | Total | ||

| January | 24 | 162 | 200 | 362 | 24 | 256 | 440 | 696 | |

| February | 25 | 210 | 149 | 359 | 24 | 216 | 415 | 631 | |

| March | 26 | 202 | 234 | 436 | 25 | 218 | 491 | 709 | |

| April | 29 | 210 | 219 | 429 | 27 | 257 | 479 | 736 | |

| May | 24 | 215 | 207 | 422 | 24 | 283 | 396 | 679 | |

| June | 23 | 210 | 231 | 441 | 26 | 240 | 459 | 699 | |

| July | 26 | 182 | 195 | 377 | 26 | 294 | 568 | 862 | |

| August | 27 | 216 | 220 | 436 | 25 | 198 | 390 | 588 | |

| September | 27 | 192 | 182 | 374 | 23 | 177 | 329 | 506 | |

| October | 27 | 223 | 193 | 416 | 22 | 182 | 221 | 403 | |

| November | 25 | 219 | 181 | 400 | 22 | 233 | 290 | 523 | |

| December | 28 | 226 | 185 | 411 | 24 | 227 | 340 | 567 | |

| Total | 2467 | 2396 | 4863 | 2781 | 4818 | 7599 | |||

No. of fits during the year 1881

In 1881, there were 7599 fits from an average of 48 patients. Thus a patient with epilepsy could expect to average about three fits a week. This must have had a devastating effect on the sufferer and would have been difficult for the largely untrained attendants. On each epilepsy ward (one male, one female) there were about 79 fits each week.

The majority (65%) of patients diagnosed with epilepsy from 1861 to 1900 were to die in the asylum. Some 22% recovered, though the recovery would not have been from their epilepsy, rather from a concomitant psychiatric illness.

Epilepsy had for many centuries been associated with mental disorder. In the Middle Ages it was thought to be contagious, hence the need for them to be incarcerated. This very negative view of epilepsy led to much discrimination and Connecticut actually passed laws against epileptics in 1895 which restricted their freedom of movement.

Shawn Masa and Orrin Devinsky, ‘Epilepsy and Behaviour: A Brief History’, Epilepsy and Behaviour, 1 (2000): 37.

The convulsions and postictal behaviour which could include violence, confusion and loss of memory were thought to be proof of the link between them. Later research does show a correlation between mood disorders and epilepsy and this is bidirectional; that is, those with mood disorders are more likely to suffer from epilepsy and also those with epilepsy are more likely to develop mood disorders.

Nowadays epilepsy is not seen as a psychiatric condition and a person with epilepsy is unlikely to be treated by a mental health unit. In the nineteenth century it was different as the Lifton family were to discover.

The Lifton family's experience

In 1861, when Bristol Lunatic Asylum opened, the Liftons were a fairly prosperous family. Isaac and his wife Jane had five children and Isaac’s job as a boot-maker generated enough income for them to have a live-in servant. In the 1871 census they were still all together, but shortly afterwards Isaac was admitted to the asylum three times between 1871 and 1872. He then had a further admission in 1881 and he died in 1885.

His son Sidney, the youngest of the five, had his career in the Rifle Brigade terminated and was admitted to the asylum in April 1887, followed by his son Frederick in November 1887. Both had long admissions and died in the hospital. On his wife’s side, two cousins were also residents there. The family however, were not insane; their curse was epilepsy. (Admission book BRO 40513/C/2/7, p. 214.)

"Stupid and indifferent"

On admission Sidney was described as ‘stupid and indifferent’. He would not speak or reply to questions. He had been brought to the asylum by a constable who found him wandering in the street in a confused state. This seems typical of a postictal state (the period following an epileptic fit). Widdess-Walsh and O. Devinsky, ‘Historical perspectives and definitions of the postictal state’, Epilepsy and Behaviour, 19 (2010): 96–99

Later, when somewhat recovered, Sidney told them he had no memory of what happened and that he was ‘daft’. His brother Rowland, however, states Sidney had been very low prior to admission and his notes classify him as suicidal. Describing himself as daft may also indicate low self-esteem. He then went on to spent the next 11 years of his life in the asylum, dying aged 37 in March 1898.

We have three sources of evidence for his time spent there: the nursing notes, the fairly frequent assessments of the medical staff and his own voice in the form of letters written to the Medical Superintendent and the Visiting Committee.

His letters indicate he was not happy to be in the asylum. In one, he describes how ‘out in the airing court, I jumped the wall and was brought back and placed in a signal (seclusion) room for four days’. This letter shows a man proud of his career in the army and his trade as a hairdresser (as was his brother Frederick). For many men admission to an asylum was an attack on their manliness, as Marjorie Levine-Clark found in her research.

‘Embarrassed Circumstances: Gender, Poverty and Insanity in the West Riding of England in the Early Victorian Years’, Marjorie Levine-Clark,

Sex and Seclusion, Class and Custody: Perspectives on Gender and Class in the History of British and Irish Psychiatry, eds. Jonathan Andrews and Anne Digby, pp. 123–148.

This was the case for Sidney: because he was incarcerated and because he could not work, he was not a man. He had been a soldier, the height of manliness, but had to leave because of his epilepsy. His admission meant he could not work as a hairdresser and thus became labelled a pauper. He could no longer provide for his family – another slight to his manhood.

Several feminist writers including Showalter have suggested that during the Victorian era the idea of insanity became feminised. Though this approach has not been without its critics, it is understandable how Sidney felt emasculated. (For a review of the debate around gender and madness see Andrews and Digby, Sex and Seclusion, pp. 8–44.)

In his letter to Dr Thompson, the Medical Superintendent, he promises to ‘act the man’ and ‘can go out to work’. He implores Dr Thompson to discharge him, at least on a trial basis.

Nursing notes in 1887 report him as striking another patient on July 1st, and injuring his left eye on August 2nd (Admission book BRO 40513/C/2/7, p. 214). Both the nursing notes (June 14th 1887) and his own letter describe how he smashed a door with a broom. It is not clear whether these incidents were a direct result of his epilepsy or related to his anger. He obviously attracted attention as there are regular notes in the hospital medical journals and he seems to have been placed in seclusion more than any other patient during the period 1887–90. (Medical Report BRO 40513, pp. 86–90.) Whether this was for his own safety is unclear but he was given fairly frequent injections of hyoscine, a powerful sedative which a previous medical superintendent had stated should not be used for epilepsy (Early, Pauper Palace, p. 19).

Epilepsy dominated his life, but when not affected by his condition he did seem to function fairly well. There is a report of him playing in a cricket match but he became abusive (Admission book BRO 40513/C/2/7, p. 214). It is difficult to know whether this verbal abuse was related to his epilepsy. His untreated epilepsy would certainly have affected his brain but it is a mistake to automatically attribute all behaviour to a patient’s disease or condition. He was not a satisfied inmate; he tried to leave the asylum and he got into fights.

More recent research shows that following a fit, patients are likely to suffer from confusion and psychotic ideas which in 22.8% of cases lead to violence.

Kousuke Kanemoto, Yukari Tadokoro & Tomohiro Oshima, ‘Violence and postictal psychosis: A comparison of postictal psychosis, interictal psychosis and postictal confusion’, Epilepsy and Behaviour, 19 (2010): 162–166.

By April 1891 Sidney’s physical condition is described as feeble but he was to live for another seven years. He died in March 1898 (Medical Report BRO 40513/C/11/1).

His death was recorded in the Medical Report above and the Bristol Mercury and Daily Post, March 19th 1898:

‘On Saturday afternoon last he was seized by a severe epileptic fit, and the attendant who was near him loosened his tie and laid him on the ground. The deceased suddenly changed colour and although everything was done to revive him, he died within a few minutes.’

This newspaper report shows the vulnerability of those with epilepsy. Nowadays a simple injection of diazepam would have saved him but then there was no treatment.

‘Epilepsy Action’, accessed 26.9.14, https://www.epilepsy.org.uk/info/first-aid/emergency-treatment-seizures-last-long-time

Sidney’s story is certainly not a happy one. He is an example of someone who did not conform. He certainly did not understand the nature of his own condition but then nor did the institution. The condition was still in many minds associated with devilry and the bizarre and sometimes violent behaviour of those with the condition probably meant their treatment was often harsh.

Gordon Holmes, ‘Evolution of Clinical Medicine Illustrated by the History of Epilepsy’, British Medical Journal, 2(4461) (July 6th 1946): 1–4.

If the Liftons had been born now, their lives would have been very different.

Another blog in the series by Paul Tobia, edited by Karen Hooper, and published by Stella Man

Contact us about the museum